Archive for the ‘Climate Change’ Category

5 ways brands can engage on climate change

2010 tied 2005 as the hottest year on record, according to reports last week. The news came as flood waters overwhelmed Queensland, Australia and mudslides killed hundreds in southeast Brazil. The natural disasters were made worse by global warming, scientists told ABC News.

Meanwhile, a new poll shows only 40% of Americans believe global warming is caused by human activity. And New York Times environmental blogger Andy Revkin said in 2010 “global warming, the greatest story rarely told, had reverted to its near perpetual position on the far back shelf of the public consciousness — if not back in the freezer.”

Is that how it is for you? Is climate change even on your radar screen as a business? And if it is, are you doing something about it? Or are you treating it like some harmless object along the distant horizon?

What your brand can do

I won’t make an argument for why you or your business should care about climate change. I’ll leave that to authors like Bill McKibben, whose 2010 book “Eaarth” is an unsparing description of a world already scarred by global warming and a guide to how we must now live in it.

What I would offer are five ways your business brand can engage stakeholders on climate change. After all, a large minority of Americans believes humans are causing global warming and increasing numbers of customers are holding business accountable. On the opportunity side, brand differentiation around climate change is there for the taking in many markets.

- Brand as promise: You can’t waffle on climate change. Choose to believe the scientific evidence and climate scientists like this one who states unequivocally, ”We’re observing the climate changing – it’s happening, it’s real, it’s a fact.” Take a stand. Let your stakeholders know your business cares deeply about the trajectory of the world’s climate. Then show them what you’re doing about it through your products, services, operations and culture.

- Brand as meaning: Customers, employees and, indeed, all stakeholders are in constant search for meaning. That’s life. Connect what you’re doing on climate change to what matters to your stakeholders. And what matters to most of us is that we and those we care about achieve happiness and avoid suffering. The climate is now on a very unhappy path. Be an example for a different way forward.

- Brand as emotion: We all experience basic emotions such as joy, love, anger, sadness, surprise and fear. For many of us, the thought of climate change overwhelms us and triggers undesirable emotions. How much more desirable is a brand that taps into the joy and satisfaction in caring for our planet and its current and future inhabitants?

- Brand as story: Humans connect through stories. It’s how we entertain, educate, preserve our cultures and instill values. Your brand is a story. Place it within the Mother of All 21st Century Stories — climate change — and watch as new, meaningful and emotional connections get made.

- Brand as experience: No matter what we tell others about our brands, what determines their fates are the experiences others have of them. When someone interacts with your business or product, they experience your brand as a promise kept or a promise broken. Promise to be on the right side of climate change and then give others the experience of standing with you — and you with them — in creating a world hospitable to all.

There’s no disguising an unsustainable business

Apologies to the duck, but if it looks like an oil company, drills like an oil company, and speaks like an oil company, then it’s probably an oil company. And no amount of green costuming can disguise its true brown nature, especially when the promise of its “product” is now a potential ecological and economic disaster.

In the past decade, BP has positioned itself as a progressive global corporation — beyond petroleum, it would have us believe. In reality, it’s a gigantic oil company that, despite its energy diversifications, is determined to keep feeding our insatiable carbon appetite and making billions for it and its shareholders along the way.

To BP and any other business in an inherently dirty industry, spare us the green preening. A fossil fuel business is not sustainable, OK?

If only BP would be so honest. Instead it continues to lead with a brand — symbolized by a logo inspired by the Greek god of the sun and bathed in pastoral green — that implies its core value is sustaining life for the planet and all its inhabitants.

Branding consultant Lisa Merriam tells it like is:

“The much-admired green sun BP brand died this week. This is a brand that never left the marketing department. No matter what they said the company stood for, they never lived it. Despite all those smug ads about wind farms and being ‘Beyond Petroleum,’ this shows they are just like any other oil company — their green brand is as dead as all of the wildlife washing up on Louisiana shores.”

While I side with Merriam on this one, the reality is BP’s green reputation hasn’t been warranted for some time, if ever. In April 2008, Sustainable Industries magazine, citing an anonymous source, reported:

(A) top-down decision has been made to pull away from touting any “green” initiatives in the media, and in fact major “green” advertising buys have been canceled. Recent press releases focus not on alternative energy successes as they did in (former CEO Lord) Browne’s time, but on BP’s ability to keep pumping oil, maintain its oil reserves and safely conduct deep-water oil drilling.

A look at the advertising BP features on its website seems to bear this out. Beyond petroleum isn’t an environmental message; it’s an energy security message, as copy in this current BP ad illustrates:

To enhance America’s energy and economic security, we must secure more of the energy we consume. That means expanding the use of wind, solar and biofuels, as well as opening new offshore areas to oil and gas production.

BP doesn’t tout alternative energy sources to help reduce global warming — an environmental message. In fact, it clearly is trying to sway public opinion in favor of allowing more offshore drilling — a decidedly non-green initiative.

While BP isn’t hiding its desire to extract and sell lots more oil, it wants to have its cake and eat it, too: lead with energy security and have us believe it also cares about the environment. Consider this BP advertising headline, “Hydrocarbons and low carbons living in harmony.” Right. And Monsanto has some genetically modified seeds to sell you organic farmers.

BP’s website has the obligatory environmental and society sections, giving the impression of their planetary concern. But look closely at BP’s statement on sustainability:

At BP we define sustainability as the capacity to endure as a group, by:

- Renewing assets

- Creating and delivering better products and services that meet the evolving needs of society

- Attracting successive generations of employees

- Contributing to a sustainable environment

- Retaining the trust and support of our customers, shareholders and the communities in which we operate.

Hardly the rhetoric of a company committed to advancing social and environmental health through its company operations. What it tells me is BP cares most about staying in business — “to endure as a group.” The closest it comes to an environmental promise — “contributing to a sustainable environment” — is so vague as to be laughable.

BP’s two-faced approach should not be dismissed as just another instance of greenwashing. It feels more insidious, a cleverly disguised deceit on a global scale. Its incessant search for oil — even in 5,000-foot waters in the Gulf of Mexico — puts BP anywhere but “beyond petroleum.” In the name of “energy security,” BP is willing to risk the kind of ecological calamity now threatening the Gulf region. That is not a risk a sustainable company takes.

The day BP stops drilling is the day I’ll start listening. Until then, let’s make no mistake about the kind of company BP is.

The sustainable virtues of slow brand

This may be the first and only time you see the words “cathedral thinking” and “slow brand” used in the same sentence. Allow me to explain.

Last week I heard New York Times journalist Andrew Revkin refer to cathedral thinking as he spoke of his reporting on the daunting ecological challenges that confront us all. The effort needed to prevent the worst from happening will take enormous long-term commitment. The kind that compelled generations of humans past to build great religious monuments over decades, even centuries, knowing they would never experience the full fruits of their labor.

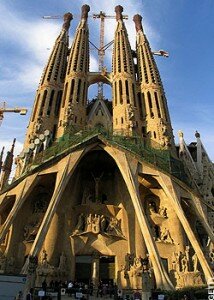

Gaudi Cathedral

I think of the Gaudi Cathedral in Barcelona, whose construction began in 1882 and continues today — 127 years later and 83 years after the death of its famed architect Antoni Gaudi.

I suppose only someone like me would ponder branding as Revkin spoke. I jotted down on my notepad the words slow brand. I had never seen or heard those two words used together, although a subsequent web search shows at least one blog by the name.

There are emerging slow food and slow money movements, but no slow brand movement. That’s understandable. Who in business wants “slow” to describe anything about them?

Painstakingly constructing a cathedral is no metaphor for how most companies and their brands are built. In the hyper-competitive world of business, speed is of the essence. We don’t know where we’re going, but we’re going there fast. We want a brand — stat!

Fast brand, slow brand

Companies that embrace the principles of sustainability will quite naturally take their foot off the accelerator. Sustainability requires a fundamental restructuring in how we conduct business. By holding itself accountable for the environmental and social impacts of its actions, a sustainable business doesn’t take shortcuts to success.

How we build our company brand matters. Weak ones are little more than facades. At best their value is aesthetic. Good ones are strong foundations. They allow businesses to stand the test of time because they’re solid, substantial, dependable, built with a sense of purpose and a whole lot of sweat equity. For me this describes slow brand — not a type of brand, but an approach to building a brand that gains strength over time.

How does slow brand compare with fast brand? Let me take a crack at drawing some distinctions:

- Fast brand is led by marketing. Slow brand is led by mission. Fast brand is isolated to marketing. The rest of the company pays it little or no attention. Slow brand supports the mission of a company, its reason for being. Just as a mission’s accomplishment requires an entire company, so does the building of a brand.

- Fast brand is how we look. Slow brand is who we are. Fast brand is obsessed with appearance: cool, innovative, powerful, smart. Slow brand is committed to substance. Integrity matters above all.

- Fast brand is a promise communicated. Slow brand is a promise fulfilled. Fast brand reduces itself to messages delivered by creative marketers. Slow brand knows a company’s actions speak louder than its words.

- Fast brand is purchased. Slow brand is earned. Fast brand loves media plans: broadcast, social, print. It works inside-out. Slow brand loves satisfied customers, employees and other stakeholders. It works outside-in.

Putting the CEO in charge

The longer I work at the intersection of branding and sustainability, the more convinced I am that brand ownership cannot be left to a marketing team. Ultimate brand responsibility must rest with the CEO. This is especially important for a business that’s making sustainability a brand cornerstone — a so-called sustainable brand. Stating a commitment to sustainability heightens the expectations of a company’s practices. And only the CEO is positioned to ensure every employee fulfills the promise of sustainability inherent in the mission and brand.

If your business is striving for sustainability, you know the transition won’t happen overnight. It will take concentrated effort over a long period of time. You may not be building a cathedral, but it may help to think you are.

How to emerge green and ahead after recession

Making the business argument for going green can be tough even in the best of times. Trying to make it during the Great Recession? Forget about it.

Or so goes the conventional line of thinking.

Consultant Andrew Winston, author of the popular book “Green to Gold,” wants you to believe otherwise. He makes his case in his new book, “Green Recovery: Get Lean, Get Smart, and Emerge from the Downturn on Top.” Winston writes:

Winston writes:

This book presents an optimistic view of what green can do for your company in hard times.

Optimistic, yes. And realistic. Winston knows the recession has knocked businesses and their customers back on their heels. There are few companies today with the financial wherewithal or stomach for large-scale sustainability initiatives.

So what’s a company to do? Winston has plenty of suggestions. His small book reads like a how-to guide for businesses, with easy-to-digest lists of pragmatic reasons and low-cost methods for becoming more sustainable.

Focusing scarce resources

He offers four broad recommendations and organizes his book around them:

- Get lean: You can generate savings fast by reducing energy costs and consumption in your buildings and facilities, data centers, distribution operations, employee travel and by reducing and recycling waste.

- Get smart: Collect data on your environmental footprint, internally and across your value chain, and make it available to the people who can best use it to create change.

- Get creative: Creativity is free. And green innovation is what will set you apart as your competitors stand still. Ask “big, heretical questions.”

- Get (your people) engaged: Winston says, “In these times of low morale, and perhaps because of the stress of harder economic conditions, many people want more meaning at work. A green focus will both engage and inspire your people to keep going through tough times.”

Reducing your environmental footprint now can create advantage over your lesser-prepared competitors. Before long, however, you and your competitors will have no choice. Powerful forces remain at work even as the current  economy struggles and squeezes profits. Chief among them are climate change and constraints on natural resources and nonrenewable energy.

economy struggles and squeezes profits. Chief among them are climate change and constraints on natural resources and nonrenewable energy.

In his conclusion, Winston writes:

As hard as it may be to imagine, green pressures will force even larger, more sustained changes in business than current economic pressures. We’re talking about a fundamental shift in how the world works.

Application to smaller businesses

Most of Winston’s examples are from larger companies. I asked Winston in an email whether his recommendations work equally well for smaller businesses.

In short, yes, all of these strategies and tactics apply very well for smaller companies. In fact, smaller enterprises may feel more strain on cash flows and need to get lean even faster. The one caveat is whether any capital is available for investment in environmental improvements.

Winston recommends setting aside a portion of planned capital expenditures for environmental priorities, such as energy reduction. He also says smaller businesses may have the advantage when asking the heretical question. “Arguably smaller companies will be less tied to the status quo and more able to foment disruptive change,” he told me.

And what about Social Recovery?

I also asked Winston why he only briefly mentions the social dimension of sustainability.

Part of the answer is based in my expertise and focus. Another is that the ideas for getting lean as a way to fund a Green Recovery need to be focused on quick paybacks, and those types of initiatives tend to be more environmental: saving money on facilities, on IT, etc. It’s harder to pursue the social agenda as a cost-saving path…That said, many companies are building strong brands by hitting themes of transparency, responsibility and corporate citizenship.

Winston comes off as a pragmatist with deep concerns about the environment and the readiness of business to deal with what’s ahead. And for good reason. A new study of 1,500 corporate executives finds only 30 percent of companies have developed a clear business case for sustainability. Another recent study of major U.S. businesses concludes:

The current state of corporate environmental policy and management is surprising, perhaps even shocking.

Seizing the opportunity

Looking past the woeful business response to our environmental challenges lies a classic business opportunity. Iconic environmental businessman Paul Hawken, speaking in Portland, Ore. this month, asserted: “There’s no such thing as bad news about the environment, only information.” And in that information lies the makings of commercial success for those paying attention.

Winston sounds a similar theme.

Some companies that had a weak commitment to sustainability may be pulling back now. What a great opportunity to lead.