Posts Tagged ‘Juliet Schor’

Taking the road less traveled on consumption

This article first appeared in Sustainable Industries, September 28, 2010.

The latest drop in consumer confidence will no doubt discourage many businesses. After all, consumer spending comprises 70 percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product.

If individuals have greater confidence in the future, they buy more stuff. Businesses make more money and hire more employees. That increases consumers’ ability to purchase more things, their confidence rises and the virtuous cycle continues.

Until it stops.

And stop it did two years ago this month after Lehman Brothers collapsed into bankruptcy and sent stock markets and the economy into a tailspin.

With today’s overall economy only modestly improved, we in business today find ourselves at a crossroads. Do we continue down the rutted but familiar road of a materialistic marketplace, hoping the road will soon smooth out? Or do we choose an alternate route to prosperity this time?

The dead end of material consumption

It didn’t take the Great Recession to teach many of us the path of consumption we’ve traveled for more than a century is ultimately a dead end. That’s been apparent for some time; we have only one planet to sustain our pace of natural resource consumption, and we need two or three at the rate we’re going.

What isn’t apparent is whether our experience of the Great Recession will fundamentally change the way we do business. Ask yourself:

- Is your business hunkering down, waiting for the return of the free-wheeling, free-spending consumer?

- Or are you using this period to rethink your business model, what you produce and sell and how you measure success—consistent with a resource- and financially constrained age?

Confronting ‘the materiality paradox’

The last time we suffered a downturn like this was the early 1980s. When we emerged from that recession, Americans went on an unprecedented spending and consumption binge that continued largely unabated until two years ago.

The era gave rise to what sociologist Juliet Schor describes in her excellent new book, “Plenitude,” as “the materiality paradox.” That is, as products became more valued as “symbolic communicators,” they grew more reliant on fashion and novelty, speeding the cycle of consumption.

“People buy more products and turn them over more quickly,” she writes. The paradox is we value goods less today, but we consume more of them to satisfy our natural desire for social meaning and individual expression.

The non-material consumer economy

If past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior, then it’s likely Americans will return to what we do better than anyone: consume. But nowhere is it written that what or how much we consume has to be identical to the last 25 to 30 years. A consumer economy doesn’t have to mean “a-consumer-of-materials economy.”

Much of what individuals and businesses “consume” is far more about experiences than stuff, such as:

- education and training, of all types

- fine arts, crafts

- music, theater, dance and other performing arts

- movies, reading, sports and other entertainment

- travel

- hiking, bicycling, skiing and other recreational activities

- digital gaming and other virtual products

That isn’t to say these and other experiences don’t have associated sustainability issues. The business challenge is to dematerialize the production, promotion and delivery of these experiences as much as possible. But businesses enjoy a head start on sustainability when their core products are experiences instead of goods.

Makers of goods can gain a similar advantage through “cradle-to-cradle” techniques such as upcycling (turning waste material or other used or useless products into new, higher-value goods).

Design for environment and sustainable design practices minimize raw material use and waste. But the jury is still out on whether better, smarter design is the “silver bullet” solution to over-consumption. At some point the prevailing materialistic mindset also has to change.

The road less traveled

The point is: A consumer economy isn’t unsustainable by definition. It depends on what and how much gets consumed. Americans are deeply conditioned to satisfy their desire for happiness and meaning by accumulating possessions. This reflects the persuasive power of professions like mine — branding and marketing — more than some genetic predisposition to shop.

Dislodging materialism as the economic status quo won’t be easy. But if enough businesses choose the road less traveled, the next three decades will look far different from the last three.

Many sustainability leaders in business are already re-conditioning customers to consume less and differently. They respect the material limits of our planet. And they recognize what customers ultimately desire — happiness, security, belonging — isn’t found on store shelves and never goes out of fashion.

There’s no consuming our way to green

I find it difficult to avoid the topic of Wal-Mart when speaking of sustainability and marketing. The company came up again today at a breakfast presentation by two professors of business from the University of Portland, sponsored by the Oregon Natural Step Network. And once again I find myself bristling at the notion of Wal-Mart playing any part in the ultimate sustainability solutions for our planet.

Spread of fashion undermines sustainability

One of America’s foremost critics of our consuming ways is Juliet Schor, a professor of sociology at Boston College. I had the pleasure of hearing her speak this week in Portland.

Among the many observations that jumped out at me in her lecture was what she called “the aesthetization of American life.” Not sure that’s a word, but the point is fast-changing fashion, long the staple of the apparel industry, is now central to the selling of many retail products. In recent years, furniture, cellphone, home electronics and other manufacturers have joined clothing makers in emphasizing the design — or aesthetic appeal — of their products. A New York Times piece yesterday, appropriately headlined “Hoping to Make Phone Buyers Flip,” helped make Schor’s point:

Like fashion or entertainment, the cellphone industry is increasingly hit-driven, and new models that do not fly off the shelves within weeks of their debut are considered duds.

I like attractive, well-designed products as much as the next person. However, when it becomes industry’s prevailing practice to change product designs with the season and encourage us to discard perfectly good items because they are no longer “fashionable,” then we have a problem. Making more of the products we buy fashion statements only encourages us to purchase more. This may bolster the financial bottom lines of producers and retailers. But it puts the world’s environmental bottom line further in the red.

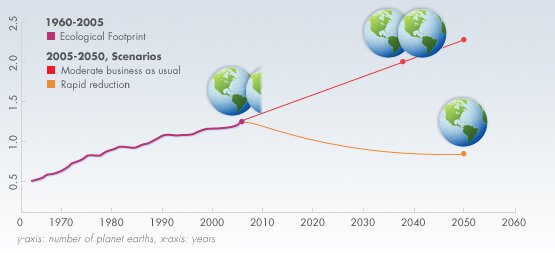

To illustrate her point, Schor projected a graph from the World Wildlife Foundation’s Living Planet Report 2006. You can access the report here. According to the WWF:

The Living Planet Report 2006 confirms that we are using the planet’s resources faster than they can be renewed — the latest data available (for 2003) indicate that humanity’s Ecological Footprint, our impact on the planet, has more than tripled since 1961. Our footprint now exceeds the world’s ability to regenerate by about 25 per cent…This global trend suggests we are degrading natural ecosystems at a rate unprecedented in human history…Effectively, the Earth’s regenerative capacity can no longer keep up with demand — people are turning resources into waste faster than nature can turn waste into resources.

WWF offers several alternatives to our unsustainable (and potentially catastrophic) “business as usual” course of human development. If you’re wondering what you can do, start by examining your consumption choices. Resist the urge to stay at fashion’s leading edge, no matter the product. Buy less stuff. When you do make purchases, reward producers and retailers who embrace sustainability.

And if it’s aesthetics you value, ask yourself this: What better designer than Mother Nature?